Our chance to meet Ezrena Marwan was an unintended one. We talked on Twitter about Desain Grafis Indonesia dalam Pusaran Desain Grafis Dunia which was released a few days back then. Right after we finished reading her interview with Justin Zhuang on Eye on Design about Malaysia Design Archive which she initiated, our editor decided to have a further conversation with her to talk about graphic design archiving.

Previously, we translated and published Ezrena’s writing into bahasa Indonesia, “Mengurai Perjalanan Desain Grafis Malaysia“. When our editor found out that they had couples of interests in common—not only about the historical dimensions of graphic design, but also on its interconnections with a larger social and political landscape, included their participations in any initiatives that promote women and gender rights—we decided to find out more about Ezrena’s view and interaction with graphic design yesgirls.

We summed up the conversations and tried to write them back into a proper interview to share theses perspectives on graphic design, nation-building and postcolonial identity, visual culture and its social dimension, and also about women and gender equality.

Have a good reading.

Why do you think history plays an important role in both current and future design practice & development?

Whether we are conscious of it or not, designers work in a historical context and make artistic choices that are shaped by history. History helps us understand why things are the way they are, why some things are possible and other not, and whether there are alternative ways of thinking and practicing design. By paying attention to history, designers not only become more aware of the historical forces that work in, around and through us, but can make more purposeful choices to shape a future that we want.

There are two interesting points of Malaysia Design Archive. First, when we (in terms of DGI) particularly workon “graphic design” instead of a wider scope of design, you work on that wider “design”. What were the reasons?

Since my main goal is to explore history, I did not want to be limited by a genre or particular form of design. After all, the different categories of design themselves have a history and change over time. Working with a broader definition, I think, also means not taking for granted the existing meanings of different categories of design, but evaluating their usefulness in analyzing the work that emerges from the Malaysian context as well as how this work invites us to rethink conventional notions of design.

Second, is the background and the goal. You said that “Design has a place in history, in nation building, and it has its own narrative—all of this is really, really important in trying to understand and articulate who we are as Malaysians.” How do you think design artifacts have anything to do with the quest of identity of one nation?

Design has always been integral to the project of nation building. The national flag is a classic example of how a design artifact is used to represent the nation. From a very young age, citizens are ingrained to identify the flag as an emblem of their country and therefore, of themselves. For me, however, looking at design is less about a quest or search for identity, as it is about understanding how design is used to shape Malaysia’s collective identity, what stories and ideas about ourselves are emphasized through a particular design, and what is left out or obscured as a result.

When graphic design products are mostly driven by market demands and commercial/capital purpose, how do you construct a reading approach to those artifacts to build a petite histoire of Malaysia’s history? Any interesting story you found out so far?

On the MDA website are a couple of Tiger beer print advertisements from 1934 featured in a Jawi newspaper, The Malay Mail. One ad features a man in traditional Malay dress of songkok and baju Melayu, raising a pint, and another a group of women in baju kurung and selendang, presumably doing grocery shopping, carrying bottles of beer in the baskets.

These ads are likely surprising to the contemporary reader because they portray Malay-Muslims as consumers of alcohol, which is considered a transgression in mainstream culture today. One might thus read the ads as evidence that Malays were more liberal in their ways back then as compared to now. We sometimes see this line of thinking among those who decry today’s cultural conservatism by, for example, pointing to mid-century images of women wearing tight-fitting kebayas as evidence that dress codes for Malay women were not always censured by fundamentalist religious views as they are now.

However, the ads might be read another way. They might also reflect the colonial ignorance of the advertising firm and the beer company, Fraser and Neave, which was founded by two Englishmen in Singapore. That is, rather than the ads being an index of Malay culture at that time, it is quite possible that the ad speaks of the company obliviousness to Malay cultural practices, wherein drinking beer is not the norm.

My point is that our interpretation of these ads reflects our own assumptions and cultural frameworks. This is not to say that we can only see what we want to see, but that it is important to be conscious of how our own contemporary lens, political views, and so on, shape how we see the world. By being aware of how we see is limited by a particular worldview, we can then begin to consider how things might be read otherwise.

The ads also show that even graphic design produced for commercial, mainstream purposes can offer rich, complex insights to how we narrate culture. The challenge is to understand through whose perspective a work of design is asking us to see, and what is kept out of sight as a result.

Iklan Tiger Beer, 1933

I believe we share a similar history as a postcolonial nation. So, how does your work with Malaysia Design Archive can relate to that fact?

Yes, Malaysia and Indonesia not only share a similar history as former colonies of European powers. In many ways, the histories and cultures of these two nations are intertwined. At MDA, I chose to organize materials according to four periods that highlight the nation’s colonial past and its gradual transition to self-governance—British colonialism; the Japanese Occupation; the British counter-insurgency against the communist guerrillas; and formal independence—rather than according to aesthetic movements or schools of thought, as is usually done in Western art history. This is not to suggest that visual culture here was not aware of developments in art elsewhere, or that Western art historical concepts are irrelevant. Rather, the periods were chosen to situate graphic design within a larger history, and to understand its uses by those in power.

What does Malaysia Design Archive do regularly?

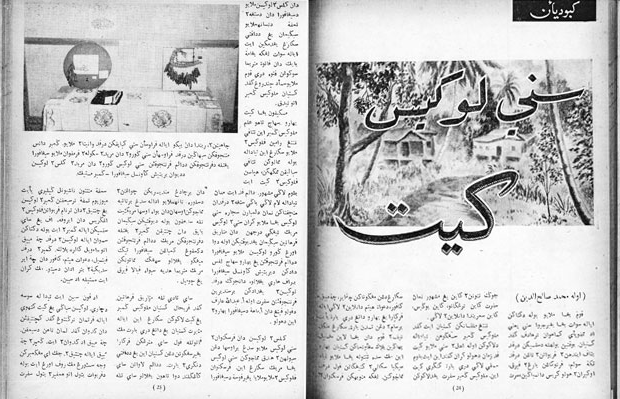

I keep an active presence on social media by sharing images from print archives or documenting Internet memes on Instagram or posting relevant articles on MDA’s Facebook page. Once in a while, I add new collections on the website. Recently, MDA collaborated with Ilham Gallery to digitize and transliterate a series of articles written in Jawi on arts and culture that were published in 1950s periodicals. The collection can be found in the new section called, Visual Arts, and more materials will be added in the future. By making these articles more accessible both online and to a non-Jawi reading public, we hope they will enrich our understanding on Malaysia’s history of arts and cultural discourse.

1954, Majalah Seni, Berbagai Aliran Dalam Seni

1953, Majalah Seni, Kisah-kisah Seni dari Pengalamanku

1950, Majalah Mastika, Kebudayaan-Seni Lukis Kita

How do you describe your graphic design practice? Whom do you usually design with and for? What subjects are you concerning the most in your graphic design practice?

Well, I mostly design in support of arts, social, rights-based organisations and initiatives that focuses on multiple dimensions of women’s rights. Organisation working on issues on women’s rights and the internet like the Association for Progressive Communications, campaigns like Take Back the Tech and Feminist Principles of the Internet. I also design for Sisters in Islam and Musawah, promoting rights of women in Islam, as well as other campaigns and projects like Freedom Film Fest and Oral History project for Pusat Sejarah Rakyat.

http://www.pusatsejarahrakyat.org/

Are you into politics? Would you mind to share how you relate your graphic design practice with your political view?

To me, graphic design is inherently political insofar as it shapes how the public visually relates to something, how it sees and understands a particular subject. That makes graphic design a powerful tool, and it also means that the practice itself is embedded in a web of power relations. I am especially interested in how women are portrayed in visual culture, how they are primarily presented in sexist ways or altogether made invisible. In my practice, I strive to draw attention to this problem and to challenge that view.

I noticed “Take Back The Tech” in your signature and figured out that we share same concern on women/gender issue. As a person who has been actively involved in this particular issue, I once tried to find out if women in graphic design industry still has to face similar problems as any other women face in daily basis, but the survey turned out to be blunt. Most of them said that there’s no particular problem as a women in graphic design industry: no discrimination, no imparity, no particular obstacles. The problems in gender issue which are too obvious for me seemed to be ways too irrelevant because of their answers—which put feminism as an irrelevant issue to be upheld in graphic design industry. Yet I assume the answers were pretty much related to the privileges they have: the economic background, the social privilege (education, literature, etc.), and many other conditions that make them have more choices compared to any other women I met outside graphic design industry. So, how do you see this women issue in Malaysia graphic design? Why do you think it’s still important to highlight the women in Malaysia design industry?

Although women make up a significant part of the design industry in Malaysia, leadership and public speaking roles are almost exclusively dominated by men. For instance, at a recent major design conference in Kuala Lumpur, all the speakers were men—not one woman was included in a single panel. When this fact was brought up, people were not even aware or did not see it as a problem. This motivated the Sejarah Wanita project. A project started by my friends and I, to archive the plural histories of women in Malaysia.

1957, Asmara, Sampul Majalah

Do you consider yourself as a feminist? And if you do, what does it mean to you?

I used to identify strongly as a feminist. While my views on gender equality have not changed, I have been reflecting on the efficacy of labels.

We both know that most narrations in history were written in male-gaze perspective, and so does graphic design history. Does Malaysia Design Archive push any special research, methods, and reading approaches regarding this condition?

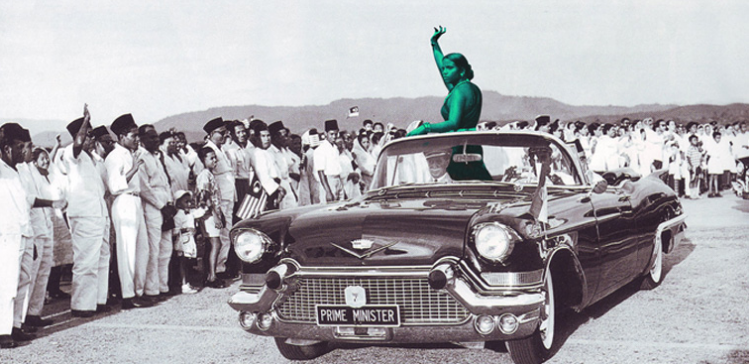

I address this issue directly in my Apa Kata series, which was created in collaboration with the NGO, Sisters in Islam, for an art bazaar/festival called Art for Grabs. The series makes us of historical photographs featuring the familiar faces of the nation’s male political leaders. These figures were edited out and replaced with other archival images of ordinary women. My intention is to challenge our usual ways of seeing leadership and nation-building, and to invite viewers to think about the role of women in all of our diversity in shaping the nation, and not just those who actively participate in the political process.

In many ways, this series describes my approach to doing graphic design history—to see what is left out in our dominant historical narratives, and to ask how our understanding of the past changes if we include those who are less visible back in the picture. This also means that our role as readers and researchers is an active one in the sense that we not only have to examine what is there, but also that we have to intervene by asking what is not there, why, and imagine alternative ways of looking.

(***)

Besides Malaysia Design Archive, Ezrena is also the person behind these following projects: Apa Kata, Take Back the Tech, and Sejarah Wanita.

Also available in bahasa Indonesia: “Ezrena Marwan: Karena Desain Lebih dari Sekadar Pencarian Identitas“.

Script and interview: Desain Grafis Indonesia/Ellena Ekarahendy.

Quoted

“Keberhasilan merancang logo banyak dikaitkan sebagai misteri, intuisi, bakat alami, “hoki” bahkan wangsit hingga fengshui. Tetapi saya pribadi percaya campur tangan Tuhan dalam pekerjaan tangan kita sebagai desainer adalah misteri yang layak menjadi renungan.”